The artistic trajectory of Paulo Canilhas has been built on a solid path, marked by rigorous training and an incessant search for dialogue between different visual languages. He attended the Advanced Course in Fine Arts at AR.CO – Center for Art and Visual Communication, where he consolidated the technical and conceptual foundations that would serve as a basis for his work. From early on, he revealed an interest in collective experimentation, becoming co-author of the Núcleo de Artes Plásticas do Laranjeiro (NAP), alongside sculptor and professor António Júlio.

His connection with António Júlio deepened through a one-year artistic residency held in his studio in Almada. It was in this context that Canilhas developed a project focused on painting and its direct relationship with sculpture, an experience that allowed him to cross disciplines and expand the boundaries of his expression. His contact with the exhibition world went beyond artistic practice. In 2014, he worked as a curatorial assistant at the MAC – Movimento Arte Contemporânea gallery, where he gained experience behind the scenes of the art market. This period also gave rise to the exhibition “Mind the Gap”, which presented to the public works resulting from this immersion between creation and curatorship.

His work reflects a careful observation of human relationships, exploring the tensions and balances between the individual and society. Often starting from personal experiences, his intention is universal: to mirror situations and offer the observer the possibility of recognizing themselves in the works. Questions such as what each person is capable of overcoming to achieve their goals, or how we adapt to the collective, are themes that run through his visual narrative.

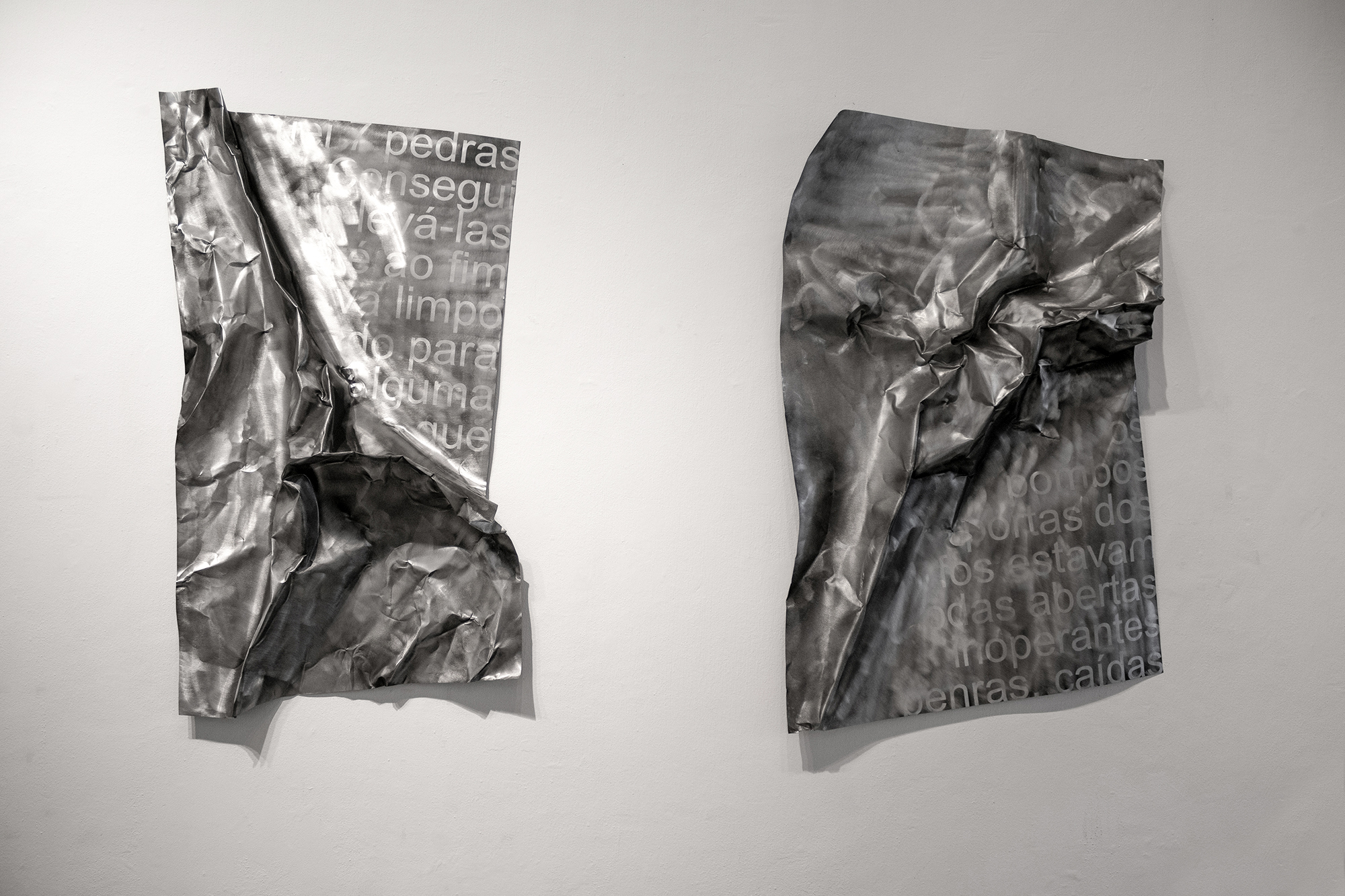

Canilhas also has a distinctive characteristic: he rejects the idea of the isolated piece. He prefers to work in series or multiples, creating collections that connect through strong graphic and aesthetic affinities, reinforcing the idea of an internal dialogue within the work itself. Today, Paulo Canilhas is represented in private and institutional collections, both nationally

and internationally.

His career, also supported by a scholarship from SILOGIA – Workplace Solutions, reveals an artist who combines the consistency of academic training with the boldness of practice, creating a singular language that continues to expand. In this interview, he shares the origins of his path, the motivations that drive his creation, and his vision of the role of the artist and art in contemporary society. A conversation that opens the doors not only to his studio but also to the thinking that sustains his practice.

What’s your artistic background?

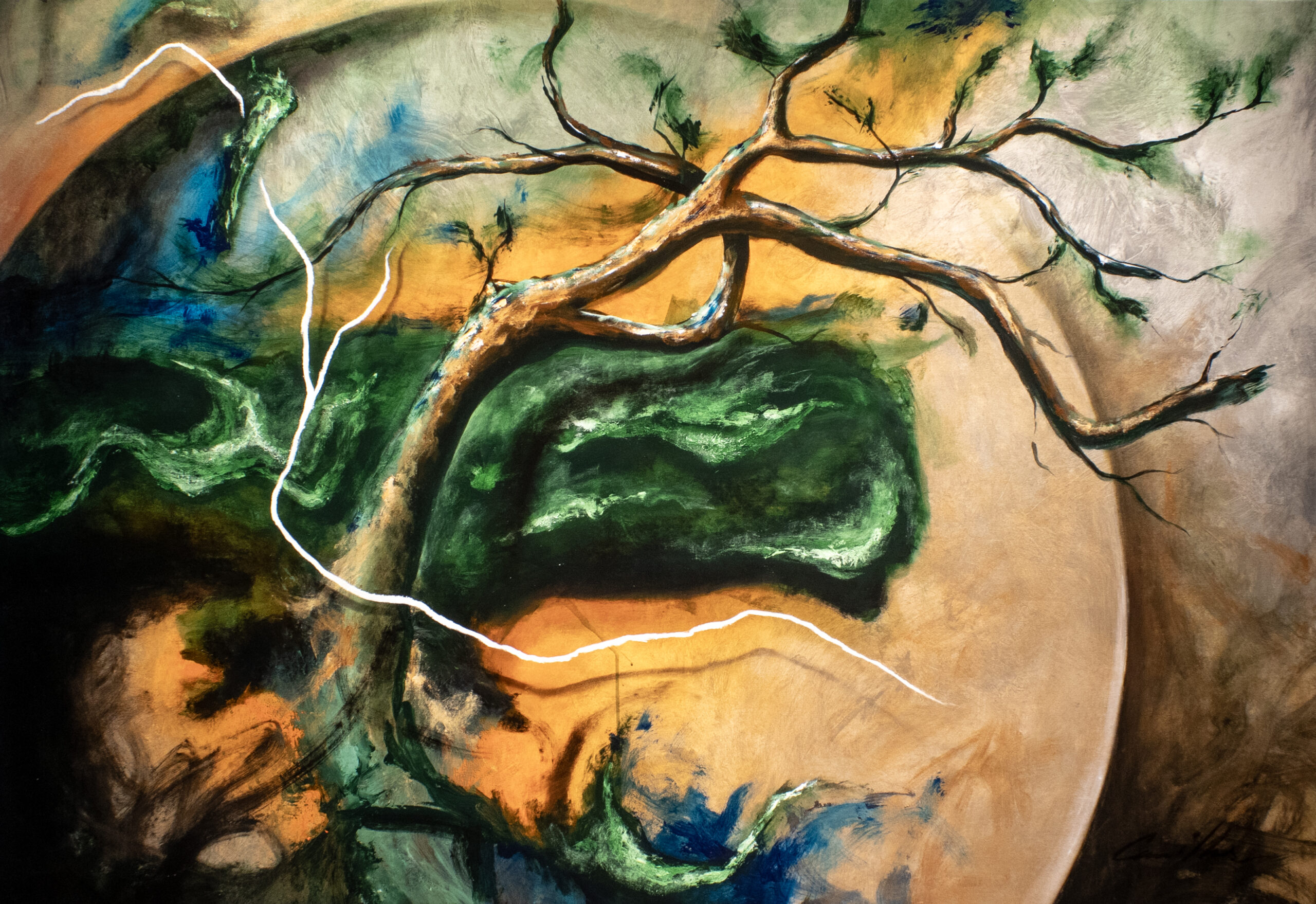

From a very early age, drawing and the handling of materials attracted me with an almost instinctive force. There wasn’t a “moment” when I became an artist; there was an accumulation of gestures, choices, and silences that shaped that path. After secondary school, I began to take this activity very seriously and never stopped. I experimented with materials, styles, and media until, at a certain point in my journey, I realised that, for me, the most important thing was the concept, the idea behind everything. Since then, I have developed themes that I explore through painting, installation, photography, and performance, tools I use to give form and a language to an inner world.

What’s integral to the work of an artist?

Integrity. The ability to remain faithful to one’s vision and, at the same time, listen to the world. The sensitivity to capture the invisible, what is not said, what hides between lines, and the courage to turn that into visible, tangible form and show it to the public. And then, of course, the work. A lot of work. Even when inspiration fails, the continuous act of making keeps art alive and creates a path.

What role does the artist have in society?

The artist is, at times, a mirror, a beacon, or even a “stone in the shoe,” but above all is another member of society, with all the flaws and virtues that we all carry. It is not only their role to illustrate the world, but also to question it (as we all should), to dismantle it and rebuild it with new possibilities, which are then made available to everyone to be appreciated and criticised.

What art do you most identify with?

I identify with art that does not seek to please. The kind that raises doubts instead of certainties. That moves between the conceptual and the poetic, and that takes risks without fear of error. I like works that start from the intimate but gain a collective dimension.

What themes do you pursue?

Themes always arise organically, often prompted by personal experiences, other times by observing the world. I have worked with memory, time, silence, and displacement, not only geographical but also emotional. The project “How many ways do you have to tell time,” for example, is born of the desire to revisit objects and materials accumulated over the years, in an attempt to set them free and to free myself as well. Each piece is a capsule where time is suspended.

What’s your favourite artwork?

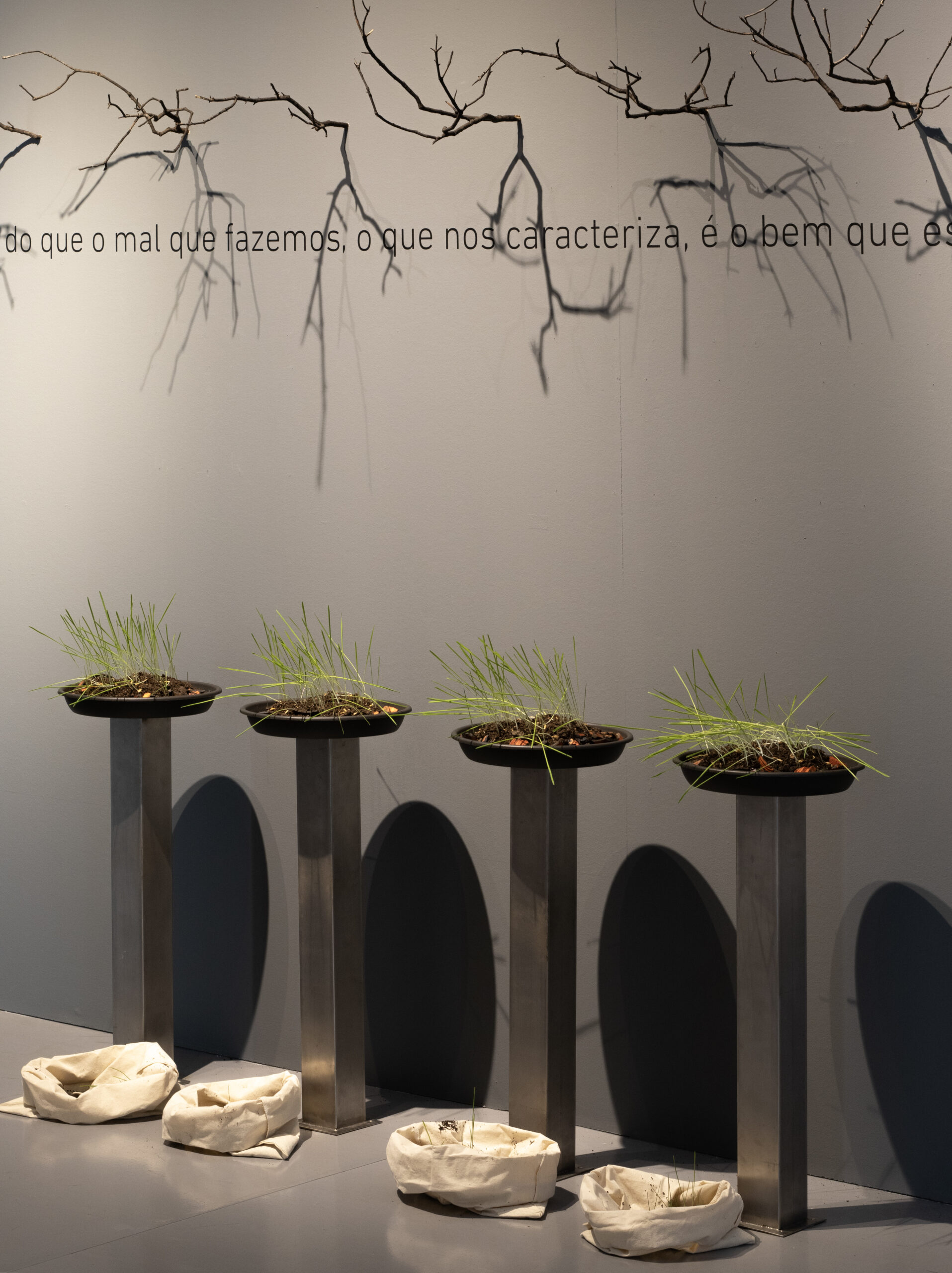

It is difficult to choose a single piece, but there are works that mark me for the way they condense a journey or open new possibilities. Rather than pointing to a specific work, I prefer to mention three exhibitions that I consider structuring in my path: All Around, at Galeria Vieira da Silva; Lastro, at Galeria Ógiva; and, more recently, the MONSANTO exhibition at Auditório Augusto Cabrita. Each brought together a set of works that, in unison, functioned like a large sculptural-emotional body. If I had to choose one work from each: Trying to find a way, in Loures; Self Portrait, in Óbidos; and Alvos in Barreiro.

Describe a real-life situation that inspired you.

More broadly, there is a very old memory that became recurrent in my imagination: as a child, building play objects (houses, boats, bridges, etc.) with wood scraps collected from a carpentry workshop owned by one of my uncles, in the Alentejo. Bags and bags of small blocks of various types of wood were brought home to then give shape to ideas that arose spontaneously during hours of play with these materials. That pleasant and happy image surely influences the path I followed in the arts, above all in the relationship I establish with materials and in the way I explore the idea of time or retained memory.

What jobs have you done other than being an artist?

Over the years, my path has crossed with other creative functions: graphic design, scenography, and visual communication projects. All these experiences have nourished my artistic practice. Work that demands listening, adaptation, and an ability to synthesise, skills I carry into my studio, a place of continuous experimentation.

Why art?

Because it is what allows me to exist in an expanded state. Because it is where I can bring chaos and control together. Because only through art can I communicate and translate things that I don’t fully understand myself, but that I need to say. Art gives form to intuitions and visions, and when at a certain point in our lives we discover that, we never again want to be without that freedom.

What is an artistic outlook on life?

It is to look at the world always with attention and a certain strangeness. It is to see beauty in a rusted surface, or hear music in the repetitive sound of a train, or the wind. An artistic outlook is, at its core, a gaze that does not conform. It is always searching for meanings, even where apparently there are none. It is a way of being that accepts the unfinished or the mistake as part of the truth.

What memorable responses have you had to your work?

Some of the most striking reactions came from people who, unexpectedly, saw themselves reflected in very personal works. It has happened that someone stood for long minutes in front of a piece in silence, and then told me a story they imagined while observing the work, surprising me with the detail and imagination. These reactions are precious, because they mean the work became a mirror or a safe harbour. And, more practically, I cherish the moment when canvases or an aluminium installation are acquired to integrate an international collection, not only for the validation, but for the realisation that that object spoke a universal language.

What food, drink, song inspires you?

I wouldn’t say there is a direct link, but there are atmospheres that put me “in the right state.” A glass of red wine in the company of good friends. A simple and honest dish like a modest açorda d’alho. If all this is accompanied by music with texture, like that of Nick Cave, Tom Waits, or the vocal ambiences of Laurie Anderson, then it will be perfect, and the mood for artistic creation is easily set.

Is the artistic life lonely? What do you do to counteract it?

Yes, it can be solitary, but it is a chosen solitude that allows me to listen better. Essentially, it is no different from other creative fields. To counter the excesses of that seclusion, I try to balance it with conversations with other artists and friends, or moments of sharing with those who understand this slightly less conventional rhythm, with family. Lately, also a bit more physical activity. However, the truth is that the solitude of the studio is, very often, a space of freedom.

What do you dislike about the art world?

Speed. Art needs time to be made, to be looked at, to be absorbed. The art world, like other cultural sectors, today lives by a logic of spectacle and urgency. There is a hunger for novelty that does not always respect the internal rhythms of the creative process. I am part of this dynamic… From a more internal and local perspective: the lack of critique of artists’ work, the few opportunities, and the limited institutional support.

What do you dislike about your work?

Working in this field is working 24/7: at every moment the projects are on your mind; at every moment a detail is important to save for later; at every moment all things are relevant. And there are days when this weighs on you. Then there is also a constant restlessness, I’m never completely satisfied. A work is finished and all I want is to start another to correct what did not match the idea or the project I had in mind at the beginning. However, it is these mechanics and dissatisfactions that give me satisfaction in working in art.

What do you like about your work?

I like the freedom it gives me to experiment, to make mistakes, to start again. I like the surprise, many times I start from a clear idea and end up somewhere completely unexpected. And I like the fact that my work manages to touch other people, even when it is born from something deeply personal. That bridge between the personal and the collective is one of the most interesting things that art allows me to experience.

Should art be funded?

Yes, absolutely. Art is a common good. It feeds critical thinking, promotes dialogue, and has an active role in the cultural construction of a society. Funding art is protecting the right to diversity of thought, to enjoyment, and to imagination. A society that invests in art invests in itself.

What role does arts funding have?

Funding enables creative freedom. Without it, many projects could not exist, especially the most experimental or conceptual, which do not mould themselves to market logics. Supporting art is opening space for divergent voices, for non-conventional formats, for approaches that question instead of confirming. Institutional support, when well structured, is a driver of cultural innovation and inclusion.

What is your dream project?

I would like to develop a large-scale installation in an unusual space, perhaps, an abandoned industrial structure or a former public building, where I could articulate sound, objects, light, and human presence (performance). A place that, in itself, already tells a story and could be reactivated through the work. An immersive, sensorial project that creates a pause in the rhythm of everyday life.

Name three artists you’d like to be compared to.

I do not feel comfortable with comparisons, but there are artists whose paths I admire deeply: Christian Boltanski, for the way he works memory and absence; Doris Salcedo, for her brutal delicacy; Rebecca Horn, for the poetic intensity of her objects and performances; Joseph Beuys; Anselm Kiefer; or the Portuguese artists Cabrita Reis and Julião Sarmento… but let it be clear: I am far from feeling comparable to these great names of art world.

Favourite or most inspirational place?

My studio is, without a doubt, the place where everything makes sense. But there are also “external” places that activate me internally, depending on the work I am developing at the time, Monsanto, for example. A territory where nature and thought coexist with a very particular intensity. Working in that space is becoming more than an artistic project; it is a reunion with the essential, with memory, with a certain secular spirituality that the landscape imposes. I like places where time seems to be suspended.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

From someone who used to greet me with the phrase “everything in order? … like disorder” (“tudo em ordem? …como a desordem”) and who once told me: “Keep going, even when no one is watching.” This advice, seemingly simple, carries enormous weight. It reminds me that what is essential does not depend on visibility, but on consistency, on inner listening, and on the courage to remain in process. Art lives on persistence, and that continuous, invisible gesture is what builds a path with truth.

Professionally, what’s your goal?

I want to consolidate my international presence and create a stronger network of dialogue with other artists and curators. More than “showing abroad,” I want to build bridges that are fertile and stimulating. I want to continue making works that do not serve only to decorate, but to summon, memory, the body, thought.

Future plans?

The present is Monsanto, the project developed in partnership with and by invitation of Quercus. The more immediate future will be, I hope, its continuation. I am preparing developments of the project that involve installation, photography, and performance, crossing fieldwork with a more immersive plastic reflection. There is also the desire to publish an edition that documents this process, not only as a record, but as a poetic extension of the work itself. The essential thing is this: to continue working honestly, respecting the time of places, the time of works, and my own time.